- Home

- Patrick Millikin

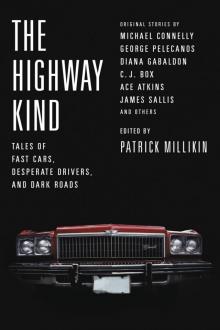

The Highway Kind

The Highway Kind Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

Newsletters

Copyright Page

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

I can only suspect that the lonely man peoples his driving dreams with friends, that the loveless man surrounds himself with lovely loving women, and that children climb through the dreaming of the childless driver.

—John Steinbeck, Travels with Charley

Stealing a man’s wife, that’s nothing, but stealing his car, that’s larceny.

—James M. Cain, The Postman Always Rings Twice

PREFACE

ON A DRIVE from Phoenix to Colorado Springs recently, I pulled over east of Holbrook, Arizona, where a thin strip of weedy asphalt wound in and out of view. This remnant of Route 66 soon disappeared as it merged with the interstate for several miles, then branched off again to continue its path. As I drove on to the sound of freight cars clanking on the nearby railroad line, the years seemed to slip away and I found myself transported into the country’s recent past. For decades, Route 66 connected travelers from the east to the “promised land” of California, serving everyone from Depression-era Okies fleeing the dust bowl to an endless succession of young would-be actresses seduced by the allure of Hollywood. Military convoys utilized it during World War II, and later, in the 1950s and ’60s, hell-raising teenagers drag raced hot rods on the two-lane blacktop. The iconic route bore witness to a remarkable period of change and upheaval.

When President Eisenhower signed the Federal Aid Highway Act in 1956, he launched the immense interstate system that would create unprecedented ease of movement around the country. This signaled the demise of Route 66 and other venerable roads and in some ways marked the end of our innocence as motorists. Roads meant everything to the country, and then they meant something else. With high-speed thoroughfares came convenience, but also anonymity and a dramatic rise in interstate crime and accident-related deaths (up until the early 1960s, seat belts remained optional in many vehicles). Postwar prosperity ushered in a golden age of the country’s car culture: the middle class was on the rise, gas was cheap, and in Detroit the race was on to create the biggest, the most luxurious, the fastest cars. Americans were going places, and mobility equaled freedom. It is an easy era to romanticize now: a time of sleek, big-finned sedans, when knowing one’s way around an engine symbolized masculinity, and owning a car meant a literal sort of empowerment.

We live in a vastly different world today, but many of us still spend significant portions of our lives alone in our cars. Over the years, the automobile has come to represent not just our freedom, but our isolation. For many Americans, driving is the closest we’ll get to a meditative state. When we’re not checking our e-mail or text-messaging with our friends, we’re driving and we’re thinking. We silently plot crimes, decide to quit drinking, sneak cigarettes, muster the courage to leave our husbands or wives, binge on fast food at anonymous drive-ins. Our cars facilitate our secret lives.

And perhaps this is because roads remain the most democratic of all our institutions. For the moment, anyway, we’re free to roam wherever and whenever we wish (if we can afford to do so), and the roads connect us, from the lowliest barrio to the most exclusive neighborhood. Follow a lowered ’60s Impala, a Honda minivan, or a new Mercedes S-Class sedan, and you’ll likely end up in three very different places, listening to three very different stories.

American crime fiction and cars have been accomplices from the beginning, partly because they both developed during the same time. The classic Western loner became, in urban America, the hard-boiled detective maneuvering down the mean streets in his car. The mythology of the Old West depended on an American wanderlust that nicely translated from the horse to the automobile, and the terse and tough realism defined by Hammett, Chandler, and Cain (among others) has always owed more of a debt to Natty Bumppo and Huck Finn than the British drawing room. At its best, crime fiction in this country remains a kind of outsider art form, providing a street-level view of the American landscape.

Tales of Fast Cars, Desperate Drivers, and Dark Roads is the subtitle for this collection of car-inspired stories, and to be sure, the reader can look forward to equal measures of all three. When I solicited the authors, I kept the guidelines pretty loose in order to encourage as many different approaches as possible. The stories were to be about “cars, driving, and the road.” I expected a provocative mix of visceral, plot-driven stories and more outré existential tales; what I didn’t expect was the deeply personal, almost confessional tone that many of these stories possess. Ben Winters establishes the mood with his opening salvo about a veteran car salesman and a test drive gone horribly wrong. Willy Vlautin writes the aching tale of a middle-aged housepainter, a Pontiac Le Mans, and a young kid’s painful coming of age. George Pelecanos contributes a moving elegy to the Vietnam era, when Mopar was king and young men raced cars in the night. Then there’s Diana Gabaldon’s inventive reimagining of a notorious real-life Autobahn accident in Nazi Germany as narrated by Dr. Ferdinand Porsche, not to mention Joe Lansdale’s unforgettable tale of two kids on the road during the Great Depression. Luis Alberto Urrea rounds out the collection with his surreal story about an old man bent on vengeance, a tricked-out VW bus, and a cartel boss known as El Surfo. These are but a few of the varied treasures to be found herein, so whether you’re a gearhead or just someone who digs a good exciting tale, you’re in for a wild ride.

Patrick Millikin

TEST DRIVE

by Ben H. Winters

I WAS GIVING it to this SOB with both barrels, boy. I tell you—I was laying it on thick.

“This vehicle right here, this is the real thing,” I told the test driver, and I was giving him my usual go-getter grin, my usual just-us-fellas wink. “Minivan or no minivan, this thing is the real deal. It looks like a dad-mobile. Right? And it is priced like a dad-mobile, especially when you buy it from us. But hey—you feel that? You feel that right there?” The engine had given a little kick, perfect timing, just as the guy eased it out of the space. “It doesn’t drive like any dad-mobile, now, does it? No, it does not. Pardon my language, sir, but hell no, it does not.”

I widened the go-getter grin. I eased back in the shotgun seat, tugged on the seat belt to get myself a little more breathing room. The test driver’s name was Steve. I hadn’t caught the last name, if he’d offered one, but that didn’t matter. I’d get the name when he signed the contract. A test drive takes all of fifteen minutes; it would take another forty-five to do the paperwork; I’d be home with a beer, celebrating my fourth sale of the week, by seven o’clock. I whistled a little through my teeth while Steve maneuvered the 2010 cobalt-blue Honda Odyssey out of the lot and headed west on Admiralty Way along the water.

That’s the test drive: the long block down Admiralty, right on Via Marina, another right on Washington, then one more right and you’re back on our lot. A quick loop, but plenty of time to get a man to fall in love with the vehicle. But those Odysseys, boy? Especially the 2009s, 2010s, those third-generation Odysseys? Well, I’ll tell you something, they really do sell themselves.

“That’s a V-six engine in there, three point five liters, and you can feel it, right? I don’t care how much tonnage a vehicle is, I really do not. You give me a darn grand piano an

d you slip this V-six in it, the thing’s gonna drive.”

Steve grunted, the first noise I’d heard from him since we got in the car, but his expression did not change. I knew what I was dealing with here: tough customer, cold fish, not about to let himself get conned by some smooth-talking-salesman type. Et cetera, et cetera. Listen: I’ve seen ’em all. I was not concerned. I could handle the Steves of the world.

“You’re right, my friend. Let’s just enjoy. You just drive and enjoy.”

He gave me a sidelong glance and I gave him the wink again, the magic wink: Just you and me out here, pal. Wife’s at home. No kiddies. Just two men talking, and it’s men who know what makes a car a car. But Steve was not a smiler. His hands were tight on the wheel. He was a little old for a soccer dad, I noticed. His hair was gray at the temples and retreating from his forehead. He drove exactly at the posted limit. His eyes were blue and watery behind thick glasses.

I sighed. I looked out the window, watched the late-day surf rush against the beach. I didn’t need this grief, this pain-in-the-ass, late-day closing-time hard-case test drive. I was the manager, wasn’t I? I was running the whole show down there at South Marina Honda. I was doing the test drive only because I liked to do test drives every now and then. Keep my ear to the ground, if you know what I mean. Keep my dick in the soup. And I seen this fella, this Steve, giving Graham a cold look and heard him saying, Who do you got who’s been around a while?

That was me. I been around a while.

“Okay, so you just wanna make this right here, when you get through the light. We’ll take her around the block, and when we get back, you know what you’re gonna say?”

Steve sniffed. “What?”

Miracle of miracles! The man could speak!

“I’ll take it. You are going to sign the papers and drive home in this gently used 2010 Honda Odyssey. You mark my words.”

“We’ll see,” said Steve, lips tight, teeth clenched. Showing me he was no sucker. Showing me who was the boss in this situation. But he was wrong. I was the boss. I was always the darn boss.

Steve took the turn, kept the thing at an even forty-five, letting cars stream past us on the left.

“So you live right around here in the area, Steve?”

“No.”

“No? Oh—here—so hang a right just here, after the light. We’re going to go around the block, the long block here. There you go. So where you down from, then? Malibu? Bel Air, maybe?”

I chuckled. This was a joke. The man was not from Bel Air. Not in that bargain-bin windbreaker. Not with that haircut. Steve didn’t laugh.

“Folks come down here from all over the city looking for a deal,” I told him. “They hear about us, they hear we’re the guys that are wheeling and dealing. They hear our ad.”

“‘When you hear our deals, your ears won’t believe their eyes,’” sang out Steve suddenly, loudly, and I laughed. I slapped my knee.

“Our commercial!” I said. “You’ve heard it!”

But that was the end of it. My test driver was all done being convivial. His eyes stared straight ahead. His hands stayed at ten and two. And he had this look on his face like...well, I don’t know what to call it. Whatever he was looking at, it wasn’t Washington Boulevard. It wasn’t the world around him. He was looking at some memory, this guy, or looking at the future. I don’t know. His eyes, though, man. This guy’s darn eyes.

I mean, look, you always get cuckoo birds out there. Alone in a car with a stranger, driving around in circles, that’s just the name of the game. You get people who think a test drive is therapy; people who think it’s The Dating Game; people who think they’re in a confessional booth. One time, poor Graham had a fella who pulled over on the side of Via Marina, asking Graham to suck his ding-a-ling. I liked to rib Graham about that one. Anything for a sale, Graham, I liked to say. Anything for a sale!

“All right, Steve,” I said. “So tell me. Where are you from?”

“Indiana,” said Steve in that cold, shovel-flat voice of his. “Vincennes, Indiana.”

“Huh,” I said. “Well.” I mean, Indiana? What the hell do you say to that? “You’re a long way from home.”

Steve grunted. The more time I spent sitting next to this guy, the less comfortable I felt, and I gotta tell you, I have a very broad tolerance for strangeness. That’s how you get to be manager, you know? That’s one of the ways.

“All righty,” I said. We passed the Cheesecake Factory. We passed Killer Shrimp. “And how many kids you got?”

“Zero.”

Now, that pulled me up short. Zero kids was even weirder than Vincennes, Indiana. I have sold a lot of Odysseys over a lot of years, and every one of them was to a parent. Soccer moms and lawn-mower dads, lawn-mower dads and soccer moms. Same as with the Toyota Sienna, same as with, I don’t know, the Kia Sedona. You’re talking minivans, you’re talking young couples, you’re talking about hauling the kiddos around, volleyball practice and ballet class and all the rest of it.

“Stepkids?” I ventured, and Steve shook his head tightly, and now I did not know what to say. Was I supposed to make some kind of joke here? So what are you, then, Steve? Scout leader? Child molester? But I didn’t even try it. Not with that look on the man’s face, that faraway stare, that death grimace, whatever you want to call it.

Next thing, he blew past the right turn back onto Admiralty.

“Hey—hey, now. That was—hey!” I craned around, looked down the roomy interior of the Odyssey and out the back window, watched a string of other cars making the right. I turned to Steve. “You missed it, man. You’re gonna have to make a U-turn, just up here—”

But Steve hadn’t made any mistakes. No, sir. He stomped on the accelerator, and the V-6 roared.

“Whoa,” I said. “Hey!”

His cheeks were pale; his knuckles were tight and white; his eyes stared darkly down the road. The word came to me then, the word I had been feeling around for. The word for that look on the man’s face: purposeful.

“I did have kids, you see,” said Steve, and he careened the Odyssey across three lanes toward the entrance to the 405. Horns bleated around us. “But they’re dead. They’re all dead.”

“I will tell you the whole story, Mr. Roegenberger,” said Steve. “It won’t take long.”

That’s me, I’m William M. Roegenberger, although I can tell you for a fact that I hadn’t told Steve that. I never introduced myself with my last name, my last name is just too much of a mouthful for customers to deal with. “I’m Billy” is what I’d said, same as I always said, when we were getting into the Odyssey for the test drive.

But here we were, him calling me by the name I’d never told him, and we were on the 405 barreling northward in the HOV lane, and my tight-lipped test driver had started talking at last and now he would not stop. He gunned that engine and gunned it again, taking the Odyssey up past ninety miles an hour, his hands still driver’s-ed correct, leaning forward and talking nonstop.

“We were on the way home from a soccer tournament. This was our car. This exact car. 2010 Honda Odyssey LX. Same color. This exact same car.” He lifted one hand off the wheel and made it into a fist, punched the steering wheel three times: exact...same...car. Exits for Mar Vista and Bundy Drive flew past outside the window. I looked at them with longing.

“Sean played in a lot of tournaments. That’s my boy, Sean. Thirteen years old. And I don’t know if he was the best player in the state, but I do know that this was the highest-scoring middle-school soccer team in the state of Indiana, and I do know that Sean was the best player on that team. By leaps and bounds.” He did it again, made a fist and punched the wheel. Leaps...and...bounds.

I looked at the odometer. We were inching up toward a hundred and ten. Where were the cops? I thought helplessly. Where were the darn cops? Rousting hard-luck cases for public urination down on Skid Row. Pulling over black guys for busted taillights.

“Now, this particular tournament, this was in Iowa, a

nd this was the first one to take place out of state, you see? He had been to tournaments before with this team, all over Indiana, but this was special, and so we all went. Me and Katie, and the girls. Three little girls.” He took one hand off the wheel, showed me three fingers: three little girls.

What if I just...jumped out? I mean, really, I was thinking as the minivan bounced and flew, what would happen if I jerked open the door of the car and rolled out onto the highway? Well, Christ. I would smash into the road at a thousand miles an hour and my body would burst open and I would be hit by a series of cars and I would die. That’s what would happen. I would die.

“Steve,” I said. “Steve?” But he wasn’t listening. He was lost in his story.

“Now, the problem was, Angie did not want to come to that tournament. All of seven years old, and with a mind of her own. Lord, did Angie put up a stink about that one. Said she could stay at her friend Kristi’s house for the weekend. It was Kristi’s birthday, and Angie was gonna miss the whole party, but I said we all had to be there. We all had to support Sean. Even Katie said, ‘You know, maybe if she’d rather stay,’ but I said no. Absolutely not. I said she had to come. I said that. I made her.”

“Well, you know,” I said quietly. “Kids.”

“And then, of course, the twins,” he said. “Gracie and Lisa. Lisa and Grace.”

Steve had to stop talking for a second. A hitch in his voice. A spasm in the tense line of his throat.

What if I punched him? was my next thought. Just smash a hard right into his jaw, bounce his crazy head against the driver’s-side window? I formed one hand into a fist. But then what? What? Grab the wheel? Get my feet on the brakes? I had literally never hit a person in my life, and what did I think, I was going to knock this man unconscious? Was that even possible?

I let my fist relax. I focused on not vomiting. The car hurtled along the HOV lane, passing Lexuses and Beemers, passing Expeditions and Hummers, roaring past Santa Monica and Culver City, past all of twilight Los Angeles.

Phoenix Noir

Phoenix Noir The Highway Kind

The Highway Kind